BJU International, Volume 94, Issue 3: Pages 384-387, August 2004.

Ramesh Babu, Sara K. Harrison, Kim A.R. Hutton.

Departments of Paediatric Surgery and Radiology, University Hospital of Wales, Heath Park, Cardiff, UK.

Accepted for publication 27 April 2004

To determine whether physiological phimosis with or without ballooning of the prepuce is associated with noninvasive urodynamic or radiological evidence of bladder outlet obstruction.

From August 2001 to October 2002 all boys with a foreskin problem and referred to one paediatric surgeon were assessed in special clinics. Those with physiological phimosis were recruited for the study and had upper tract and bladder ultrasonography (US), followed by uroflowmetry and US-determined postvoid residual urine volumes (PVR). Data were compared between boys with and with no ballooning of the prepuce. The project was approved by the local research ethics committee and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

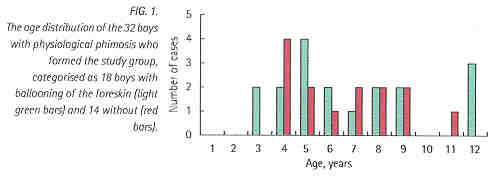

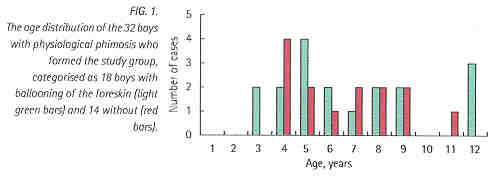

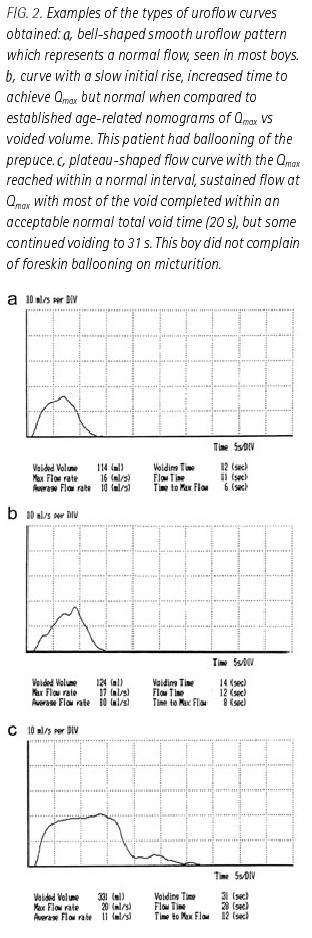

In all, 54 patients were referred for circumcision; 32 boys with physiological phimosis completed the uroflow and US investigations. Ballooning of the foreskin was present in 18 boys (mean age 6.8 years, range 3-12); 14 had physiological phimosis with no ballooning (mean age 6.5 years, range 4-11). Upper tract US and bladder wall thickness were normal in all boys. The mean maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) was not significantly different in boys with ballooning and those without (mean 15.3 mL/s, sd 4.4, range 9-24, vs 15.4, sd 2.9, range 10.7-20, P = 0.96). In addition, all Qmax values were within the normal range when correlated with voided volume and compared with age-related nomograms. Most boys had flow rate patterns showing a normal bell-shaped curve; a few (9%) had subtle changes in the flow-rate profile, with either a plateau-type curve or slow initial increase in flow and prolonged time to achieve Q(max). The two groups had comparable mean PVRs (3.5 mL, sd 5.1, range 0-18 with ballooning vs 6.1, sd 10.7, range 0-38 without, P = 0.37). Only one patient had a marginally abnormal PVR.

Physiological phimosis with or without ballooning of the prepuce is not associated with noninvasive objective measures of obstructed voiding. Minor abnormalities in the flow-rate pattern in this patient group deserve further study.

The main medical indications for childhood circumcision are pathological phimosis, usually associated with balanitis xerotica obliterans, and recurrent balanoposthitis [1,2]. Physiological phimosis is associated with a unretractile foreskin that is supple, unscarred, and said to `open like a flower' on attempted retraction [3]. In addition, although retraction may reveal a pinpoint opening, drawing the prepuce forwards confirms a wide orifice with no evidence of true phimosis [4]. Ballooning of the foreskin is also related to an unretractile foreskin [3] with a relatively narrow opening and distensible preputial sac, although ballooning as a clinical sign is not restricted to physiological phimosis, and can be seen with a normal fully retractable foreskin and in cicatrising phimosis. Most paediatric surgeons and urologists consider physiological phimosis and associated foreskin ballooning as self-limiting features of normal foreskin development [3,5], confirmed by follow-up studies with no intervention [6,7].

Both physiological phimosis and ballooning of the prepuce cause considerable parental concern/anxiety, and GPs and paediatricians frequently request surgical consultations for presumed phimosis and possible obstructed voiding [8,9]. It is unclear why, despite reports supporting the conservative management of foreskin ballooning and physiological phimosis, paediatric surgeons continue to receive `inappropriate' referrals for circumcision. Obviously one reason could be a failure of the medical profession, and particularly surgeons, to disseminate information and educate primary-care physicians appropriately. However, it may be that in an age of increasing evidence-based medicine, clinicians are concerned that previous assumptions have not been qualified with robust objective data excluding a possibility of outlet obstruction. The aim of this study was to determine whether physiological phimosis with or with no ballooning of the prepuce is associated with noninvasive urodynamic or radiological evidence of obstructed voiding.

Between August 2001 and October 2002 all boys referred to one surgeon (K.H.) by their GP with a foreskin problem were assessed in special clinic. Patients with physiological phimosis, defined as an unretractile, normal, supple, unscarred prepuce that with attempted retraction opened `like a flower' [3], were identified and divided into two groups either with or with no ballooning of the prepuce, as determined from their history. Boys with evidence of true phimosis (balanitis xerotica obliterans), active infection, other penile anomalies, e.g. minor hypospadias, symptoms of voiding dysfunction or other urinary tract pathology, were excluded.

Each boy had detailed renal and bladder ultrasonography (US) in the clinic by an experienced radiologist, after which a uroflow rate was obtained using a Urodyn® 1000 spinning-disc (Dantec, Denmark) or a Flowmate-2 recorder (Micromedics, St. Paul, MN). The flow pattern, maximum flow rate (Qmax) and voided volume were recorded and compared to established nomograms [10] to determine whether the results were within the normal range for age. Flow rates were defined abnormal if they were >2 SD of the expected normal mean [11]. Bladder US was then repeated immediately after voiding to measure any postvoid residual volume (PVR), when >10% of voided volume was considered significant [11]. Parental consent was obtained for all patients and the project was approved by the local research ethics committee. The results were expressed as means, SD and range, with statistical analysis using an unpaired Student's t-test, with P >0.05 taken to indicate significant differences.

In all, 54 boys were referred for circumcision by their GP over the 14-month study period; 37 boys had physiological phimosis and were eligible for inclusion. Four patients/parents did not agree to participate because of embarrassment or a perceived lack of time to complete the tests. One boy had his initial US but became anxious on attempting uroflow and was unable to cooperate with further testing. Thus 32 boys completed the study (mean age 6.7 years, range 3-12); 18 had physiological phimosis with ballooning of the foreskin (mean age 6.8 years, range 3-12) and 14 without (mean age 6.5 years, range 4-11). The age distribution is shown in Fig. 1. All boys had a normal unscarred foreskin and no patient proceeded to circumcision. All patients had normal US appearances of the upper urinary tract (no hydronephrosis, no hydroureter and normal echogenicity of the kidneys) and none had evidence of increased bladder wall thickness.

There was a normal bell-shaped smooth uroflow curve in 29 (91%) of the boys assessed (Fig. 2a); there was a slow initial rise and an increased time to achieve Qmax (greater than the normally expected third of the total voiding time [12]) in one boy with ballooning (Fig. 2b) and two boys with no ballooning had flat-topped, plateau-type curves (Fig. 2c). However, All Qmax were within the normal range when correlated with voided volumes and compared to established nomograms (Fig. 3). The mean Qmax was 15.3 (4.4, 9-24) mL/s in the ballooning group. The boys with no ballooning of the foreskin had a mean Qmax of 15.4 (2.9, 10.7-20) mL/s; there was no significant difference between them (P =0.96).

The patients with ballooning of the foreskin had a mean PVR of 3.5 (5.1, 0-18) mL and those without 6.1 (10.7, 0-38) mL; there was no significant difference (P =0.37). Only one patient had a PVR of >10% of voided volume (38 mL, voided volume 262 mL) despite a normal flow rate (13.9 mL/s) and is under continued follow-up.

At birth most boys have an unretractable prepuce because the inner surface of the foreskin is developmentally fused to the underlying glans penis. By a process of desquamation the two epidermal surfaces separate throughout childhood forming a complete preputial space; only 4% of newborns have a fully retractable prepuce, by the age of 3 years, 90% of boys have retractile foreskins [6] and at 16-17 years only 1% of young men have persistent phimosis [7]. Boys with physiological phimosis and ballooning of the prepuce have unretractile foreskins and are often referred by their GP for assessment of a `tight' prepuce, with a presumed need for circumcision. Griffiths and Frank [8] reported that 36 (30%) of 120 boys referred for circumcision had ballooning and 50 (42%) had an unretractile or partially retractile foreskin. Williams et al. [9] noted that 10 (14%) of 69 boys referred with penile problems complained of ballooning and 30 (43%) had a healthy unretractile foreskin on outpatient assessment. Although follow-up details are not provided for the boys treated conservatively in these reports, spontaneous resolution is to be expected, given the data provided by Gairdner [6] and Øster [7] in their papers on the fate of the foreskin. In the present study we documented 37 (69%) of 54 boys referred for circumcision as having physiological phimosis, which would indicate a high level of `inappropriate' referrals for circumcision. This prompted us to make improvements in educating local GPs in differentiating between true phimosis and the healthy unretractile foreskin.

![]() Note:

Note:

The statement in the paragraph above that "90% of boys have retractile foreskins is incorrect. It is based on half-century-old incorrect data that was supplied by Gairdner in 1949. Numerous later studies have shown this figure to be incorrect. CIRP believes that about 44% of boys have retractile foreskins by age ten. See Normal Development for more information.

Many parents are of the opinion that an unretractile foreskin and relatively narrow preputial opening, as seen in physiological phimosis, predisposes to urinary flow problems, and feel their suspicions are amply justified when they notice `alarming' foreskin ballooning. Although published data on the natural history of physiological phimosis suggests a benign, self-limiting condition, there is little objective evidence to refute these parental concerns, and to assist GPs in offering appropriate advice and reassurance. Online searches of Medline, the National Library of Medicine (PubMed), the Cochrane Library and `Turning Research Into Practice' databases revealed no articles investigating a possible relationship between physiological phimosis and obstructed voiding. In the present study, uroflowmetry in boys with physiological phimosis showed values of Qmax vs volume voided within the normal range for age, and Qmax values were not significantly different in boys with or without ballooning. These data together with the insignificant PVRs suggest that voiding efficiency in both groups is normal. Further supportive evidence of a lack of BOO is provided by the normal bladder wall thickness data.

With regard to flow curve characteristics, Segura [12] stated that `all morphologies that differ from the standard or bell-shaped curve must be considered as potentially anomalous,' and although in that paper he did not state whether the boys were circumcised or not, our few cases with abnormal flow patterns are of interest, and perhaps of some concern. However, it is well known that most of the features seen in the flow pattern of an obstructed individual can be seen in patients with normal voiding, and controversy still exists as to the value of specific flow-rate pattern analysis [13]. It is possible that a distensible preputial sac in boys with ballooning produces a dampening of response on uroflow, which could lead to a slow initial increase in flow and prolonged time to achieve Qmax. In addition, the unretractile relatively narrow preputial opening of some boys might provide a constant, physiologically unimportant restriction to flow that is nevertheless sufficient to result in a plateau-type flow curve. The significance of these rarer flow rate patterns is unclear. For example, is it possible that these abnormal flow patterns are associated with longer term problems and persistent unretractability after puberty? If this were the case circumcision could be offered appropriately at an early stage in these boys, with the aim of preventing potential morbidity related to phimosis, including painful erections and possible adverse experiences on sexual debut. Obviously, clinical follow-up data are required to assess the significance of these subtle flow-rate findings.

In this study we analysed whether physiological phimosis with or without ballooning of the prepuce is associated with evidence of obstructed voiding, using noninvasive uroflowmetry and US measurement of PVRs. These variables have been used by others as measures of voiding efficiency in children, e.g. after hypospadias repair [11,14]. Bladder outflow problems cannot be excluded by these tests and formal invasive pressure-flow studies would be required to provide definitive data excluding obstruction. However, we would consider an investigation of this type inappropriate and possibly unethical in this patient group, because of the usual self-limiting nature of physiological phimosis. A criticism of this study could be that we only obtained one data-set for each patient, as it is known that flow-rate measurements often show considerable variation within patients [13]. This was not done as we were concerned that participation in the study might be compromised if families had to stay in the clinic for several hours or attend on more than once. Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study failed to show any evidence of obstructed voiding in boys with physiological phimosis, whether ballooning was present or not.

In conclusion, the noninvasive assessment of voiding efficiency in boys with physiological phimosis with or without ballooning of the foreskin, using uroflowmetry, PVR and assessment of bladder wall thickness, showed no evidence of obstructed voiding. Normal bell-shaped flow curves were obtained in most patients. The follow-up of boys with plateau-type curves and flows with a slow initial increase would be of interest.

None declared.

Correspondence: Kim A.R. Hutton, Department of Paediatric Surgery, University Hospital of Wales, Heath Park, Cardiff CF14 4XW, UK.

e-mail: Kim.Hutton@cardiffandvale.wales.nhs.uk

Abbreviations: Qmax, maximum urinary flow rate; PVR, postvoid residual urine volume; US, ultrasonography

The Circumcision Information and Resource Pages are a not-for-profit educational resource and library. IntactiWiki hosts this website but is not responsible for the content of this site. CIRP makes documents available without charge, for informational purposes only. The contents of this site are not intended to replace the professional medical or legal advice of a licensed practitioner.

© CIRP.org 1996-2024 | Please visit our sponsor and host: IntactiWiki.